By Fernando Mercês

In our very first blogpost about VulHunt, we’ve explained what is the problem our framework solves, how it differs from common approaches to detect vulnerabilities in binaries, and introduced you to our framework’s core capabilities. As we previously discussed, VulHunt has two usage modes: standalone and agentic. In this blogpost, we’ll focus on the standalone mode, which works with VulHunt rules – Lua language scripts that interact with the core engine to detect vulnerabilities.

We’ll guide you through the process of writing a VulHunt rule for a known vulnerability in Rsync, a popular tool to transfer files over the network present in many systems. We start by understanding the vulnerability before proceeding to how we can use VulHunt to detect the exact point in the code where the vulnerability occurs.

The impacted Rsync versions range from 3.2.7 to 3.3.9. As part of the protocol negotiation, client and server must agree on a digest algorithm to verify the integrity of the file chunk being transferred. Let’s take a look at the relevant code now.

In `rsync.h` two structs are defined:

#define SUM_LENGTH 16

--snip--

struct sum_buf {

OFF_T offset; /**< offset in file of this chunk */

int32 len; /**< length of chunk of file */

uint32 sum1; /**< simple checksum */

int32 chain; /**< next hash-table collision */

short flags; /**< flag bits */

char sum2[SUM_LENGTH]; /**< checksum */

};

struct sum_struct {

OFF_T flength; /**< total file length */

struct sum_buf *sums; /**< points to info for each chunk */

int32 count; /**< how many chunks */

int32 blength; /**< block_length */

int32 remainder; /**< flength % block_length */

int s2length; /**< sum2_length */

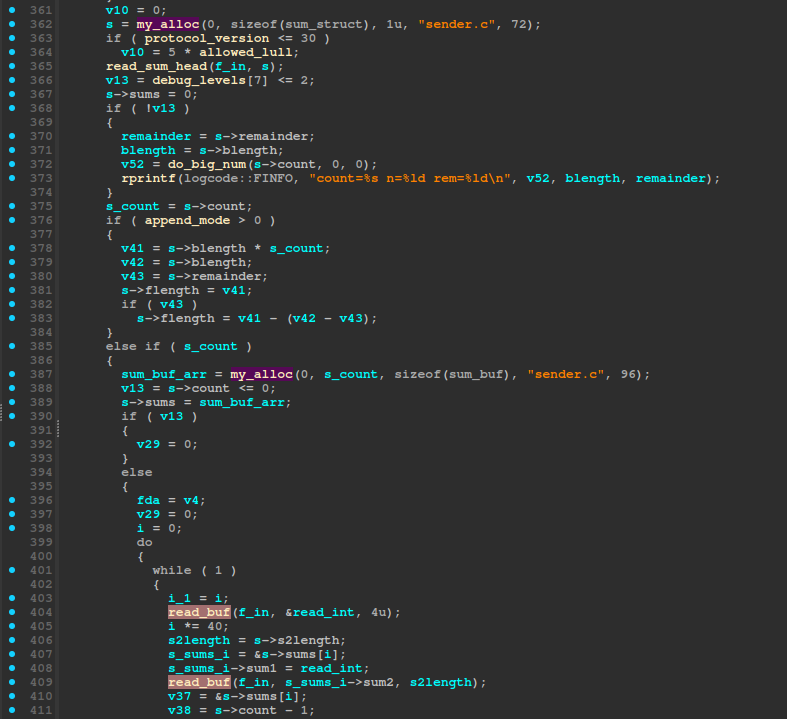

};Then, in the `receive_sums` function from `sender.c` we have:

struct sum_struct *s = new(struct sum_struct);

--snip--

s->sums = new_array(struct sum_buf, s->count);

for (i = 0; i < s->count; i++) {

s->sums[i].sum1 = read_int(f);

read_buf(f, s->sums[i].sum2, s->s2length);Both `new` and `new_array` are wrappers for memory allocation functions. The `sums` field of the struct pointed by `s` variable is a pointer to an array of `sub_buf` structs. Within the loop shown above, `s->s2length` bytes are read from `f` and written to the memory reserved for the `.sum2` field of every `sum_buf struct` in the `sums` array.

The problem is that `sum2` has a fixed length of 16 bytes and `s->s2length` is controlled by the attacker, bounded by a `MAX_DIGEST_LEN` constant. All samples we found had this value set to 64. Nevertheless, if `s->s2length` is greater than 16, it will cause an out-of-bounds write to the `sum2` buffer.

Another important thing to highlight is that `read_int` also calls `read_buf`, and it is commonly found inlined. The decompiled version of the relevant code is as follows:

As you can see in Figure 1, both calls to `new` and `new_array` were replaced by calls to `my_alloc`. Also, `read_int` became a call to `read_buf`. This is because the compiler inlines these function calls for better performance. We have to take that into account when writing VulHunt rules as function names in the decompiled code might be different from source code.

Now, if we were to draft an algorithm to detect this vulnerability, it could be:

In `rsync` binaries:

`send_file` function.`my_alloc`.`read_buf`, which copies `s2length` to `sum->sum2`.We should also make sure `SUM_LENGTH` is indeed 16, but since this was the case for all vulnerable binaries we analyzed, we’ll skip this check for the sake of simplicity.

Alright, let’s see how we translate this logic to VulHunt.

A rule is a small program written in Lua programming language that reports a result to VulHunt. It contains metadata and detection logic, where the latter is split into one or more functions. Let’s see how it works.

Each rule starts with a preamble containing rule metadata such as rule author, name, target platform and architecture, conditions for the rule to run, type libraries and function signatures needed. We start our rule with the following:

author = "Binarly"

name = "CVE-2024-12084"

platform = "posix-binary"

architecture = "*:*:*"

types = "rsync/v3.3.0/rsync"

signatures = {project = "rsync", from = "3.2.7", to = "3.3.9"}

conditions = {name_with_prefix = {"rsync"}}

scopes = scope:functions{

target = {matching = "send_files", kind = "symbol"},

with = check

}The name field contains the rule name. As we're dealing with a known vulnerability, it’s reasonable to use its identifier.

Because VulHunt also supports other targets such as UEFI modules, we tell explicitly that this rule applies only to `posix-binary` in the platform field.

The `"*:*:*"` triplet assigned to the architecture field tells VulHunt this rule will scan binaries compiled to all supported architectures (currently x86 and ARM, both 32- and 64-bit). Other possible include “x86:LE:*” and “AARCH:LE:64”. Asterisk characters mean any value and can be used in any triplet member.

As this rule applies to the rsync binary only, we set it as the component name in conditions. Think of container images containing thousands of binaries. We built VulHunt to be fast, so the conditions field allows rules to scan only on binaries that make sense.

Finally, we load any needed type library and signatures. The way they work is beyond the scope of this article, but keep in mind that a type library will improve the output of the decompiler significantly and function signatures allows our rule to find functions by name even when target binaries contain no symbols (stripped binaries).

There’s one more field required in the preamble, which is the scopes field. It tells VulHunt which scopes this rule uses. Think of scopes as strategies you want to use to find the vulnerable piece of code you’re interested in. Effectively, they set the analysis context in which the detection logic will focus on. The following scopes are supported:

In this case, we want to look for the vulnerable function by its symbol name, so we’ll be using `scope:functions` this way:

scopes = scope:functions{

target = {matching = "send_files", kind = "symbol"},

with = check

}Other possible values include `scope:project` and the powerful `scope:calls`. We’ll show how they work in a future article. For now, let’s continue.

The `with = check` part sets the checking function that will run once VulHunt finds our `send_files` function. This is where our main rule logic will be located. The function name here is not important, but `check` is a good generic name. Let’s get to the logic!

Because we used `scope:functions` with `target = {matching = "send_files", kind = "symbol"}`, we can safely assume the `check` function will only analyze the function of interest. To start small, let’s write a simple `check` function that reports a single call to `my_alloc` from within `send_files`:

if #my_alloc < 2 then

return

end

-- returns a `result:critical` table

return result:critical{

name = "CVE-2024-12084",

description = "Heap overflow in rsync",

evidence = {

functions = {

-- within `send_files`...

[context.address] = {

-- ...annotate one call to `my_alloc`

annotate:at{

location = my_alloc[1],

message = "An allocation happens here"

}

}

}

}

}

endNOTE: In Lua, a table is a versatile data type that implements associative arrays and can hold other tables as well. Tables are created with the `{}` expression.

Our `check` function takes two parameters: `project` and `context`. Let’s understand what they are for:

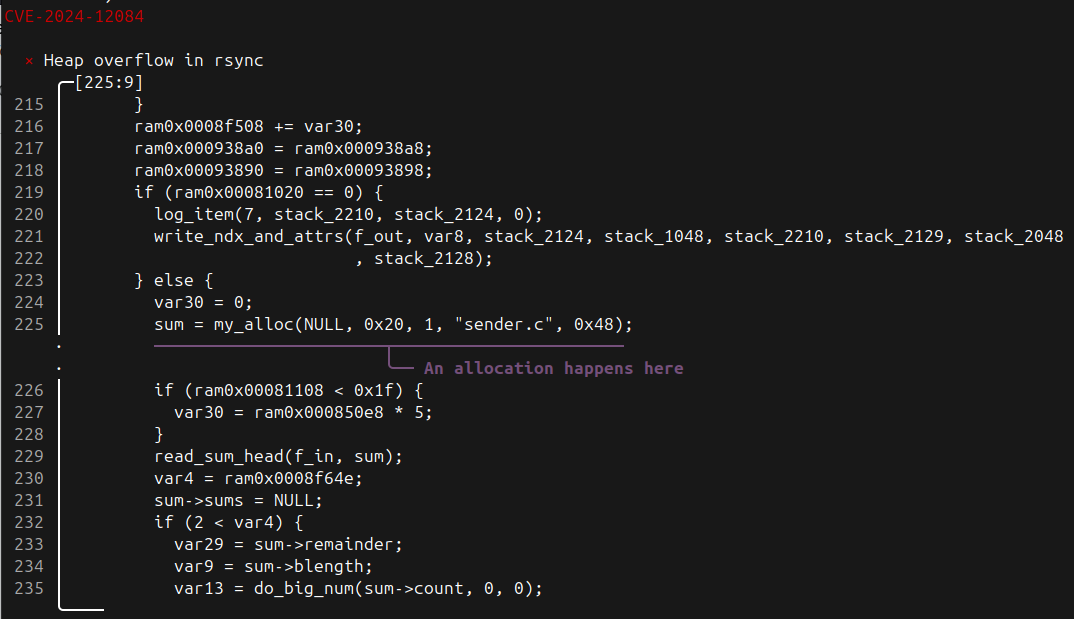

In case there are at least two calls to `my_alloc`, our simple `check` function returns a `result:critical` table to VulHunt containing three required fields: name, description, and evidence. The latter is a table that contains tables of addresses we want to annotate at. We annotate the address stored at `my_alloc[1]` with a message. In other words, this message will be added to VulHunt’s output for this call to `my_alloc` from within `send_files`. Figure 2 shows the VulHunt output produced by the command-line version when this rule is used to scan a vulnerable binary.

The example works, but it’s of course not complete. Ideally, our rule should:

`my_alloc`, not just one.`my_alloc` is not a problem per se).In the following sections, we’ll improve the rule with the above. Stick with us!

Let’s get the `send_files` function prototype annotated, cover both calls to `my_alloc`, and use more descriptive messages. Here’s a table that achieves this:

return result:critical{

name = "CVE-2024-12084",

description = "A heap-based buffer overflow flaw was found in the rsync daemon.\nThis issue is due to improper handling of attacker-controlled checksum lengths (s2length) in the code.\nWhen MAX_DIGEST_LEN exceeds the fixed SUM_LENGTH (16 bytes), an attacker can write out of bounds in the sum2 buffer.",

evidence = {

functions = {

[context.address] = {

annotate:prototype "void send_files(int f_in, int f_out)",

annotate:at{

location = my_alloc[1],

message = "This call to `my_alloc` allocates memory for a `sum_struct`, which contains\nthe `s2length` field that will be populated from attacker-controlled data"

}, annotate:at{

location = my_alloc[2],

message = "This call to `my_alloc` allocates memory for an array of `sum_buf` structures\nthat contain a fixed-size `sum2` field (16 bytes) and this array is\nlater assigned to the previously allocated `sum_struct->sums`"

}

}

}

}

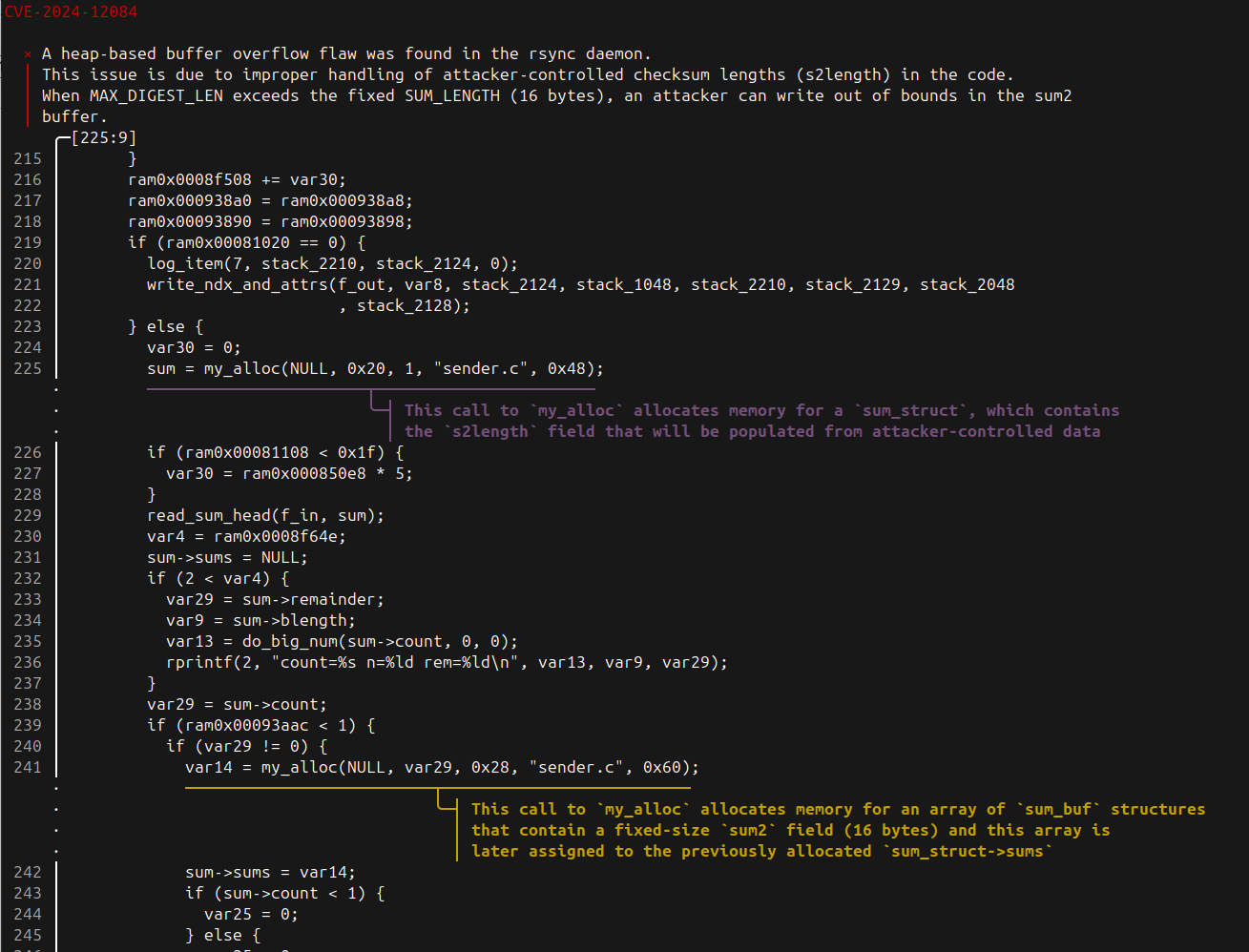

}We used `annotate:prototype` to give VulHunt more information about the `send_files` function we’re working with. Also, both calls to `my_alloc` were annotated. As a result, the output is nicer as Figure 3 shows:

The output looks good, but we still miss the most important part, which is where exactly the vulnerability occurs. Also, because we use different annotations for each call to `my_alloc`, we must ensure VulHunt gets it right.

When VulHunt sees the `context:calls "my_alloc"` code, it returns a table containing all calls to `my_alloc` from that specific context (`send_files` in our case), but the order of these function calls is not guaranteed for performance reasons. In this case though, we need to know which call comes first because we’re annotating them with different annotation messages. The following snippet achieves this:

-- get the calls to `my_alloc`

local my_alloc = context:calls "my_alloc"

-- if the number of calls to `my_alloc` is less than 2, return

if #my_alloc < 2 then return end

-- two or more calls to `my_alloc`; get the second one

local my_alloc1

local my_alloc2

if context:precedes(my_alloc[1], my_alloc[2]) then

my_alloc1 = my_alloc[1]

my_alloc2 = my_alloc[2]

elseif context:precedes(my_alloc[2], my_alloc[1]) then

my_alloc1 = my_alloc[2]

my_alloc2 = my_alloc[1]

endThen we need to use `my_alloc1` and `my_alloc2` in the table returned by the `check` function.

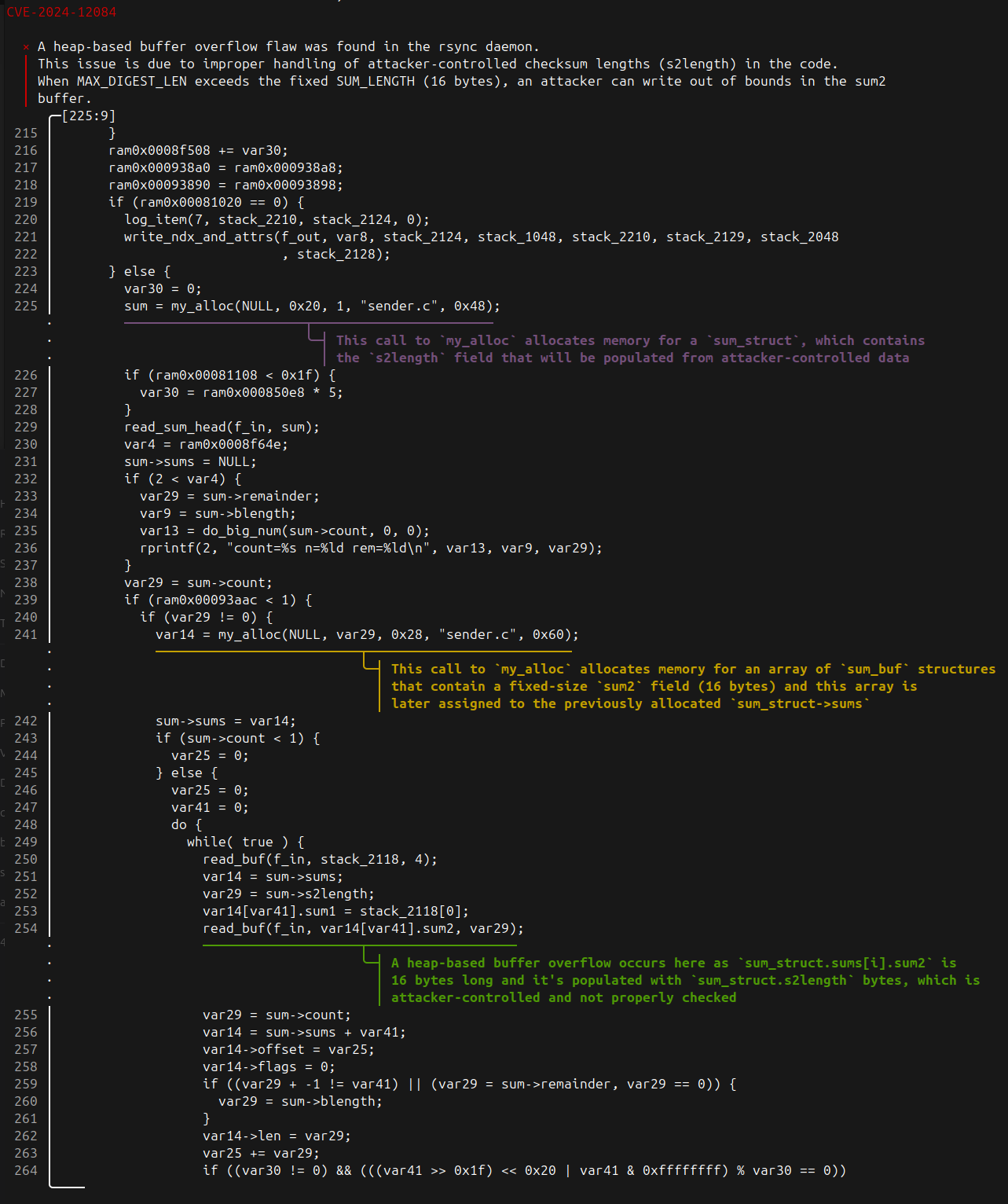

From Figure 1, we can see there are two calls to `read_buf`, but we’re interested in the second one, which is where the vulnerability actually is. As we saw in the previous section, annotating a function call normally means finding its address first. Here’s a snippet that does this for us:

-- get the calls to `read_buf`

local read_buf = context:calls("read_buf")

if #read_buf < 2 then return end

-- a variable that will hold the address of the `read_buf` call we want

local read_buf2

-- two or more calls to `read_buf`; get the second one

if context:precedes(read_buf[1], read_buf[2]) then

read_buf2 = read_buf[2]

elseif context:precedes(read_buf[2], read_buf[1]) then

read_buf2 = read_buf[1]

endOnce again, we used `context:precedes` because we’re interested in the second call to `read_buf`. Expanding the evidence table to include both annotations to `my_alloc` (now honoring their order) and to the second call to `read_buf` is seamless:

evidence = {

functions = {

[context.address] = {

annotate:prototype "void send_files(int f_in, int f_out)",

annotate:at{

location = my_alloc1,

message = "This call to `my_alloc` allocates memory for a `sum_struct`, which contains\nthe `s2length` field that will be populated from attacker-controlled data"

}, annotate:at{

location = my_alloc2,

message = "This call to `my_alloc` allocates memory for an array of `sum_buf` structures\nthat contain a fixed-size `sum2` field (16 bytes) and this array is\nlater assigned to the previously allocated `sum_struct->sums`"

}, annotate:at{

location = read_buf2,

message = "A heap-based buffer overflow occurs here as `sum_struct.sums[i].sum2` is\n16 bytes long and it's populated with `sum_struct.s2length` bytes, which is\nattacker-controlled and not properly checked"

}

}

}

}

Our output has now reached a level of completeness we can be proud of:

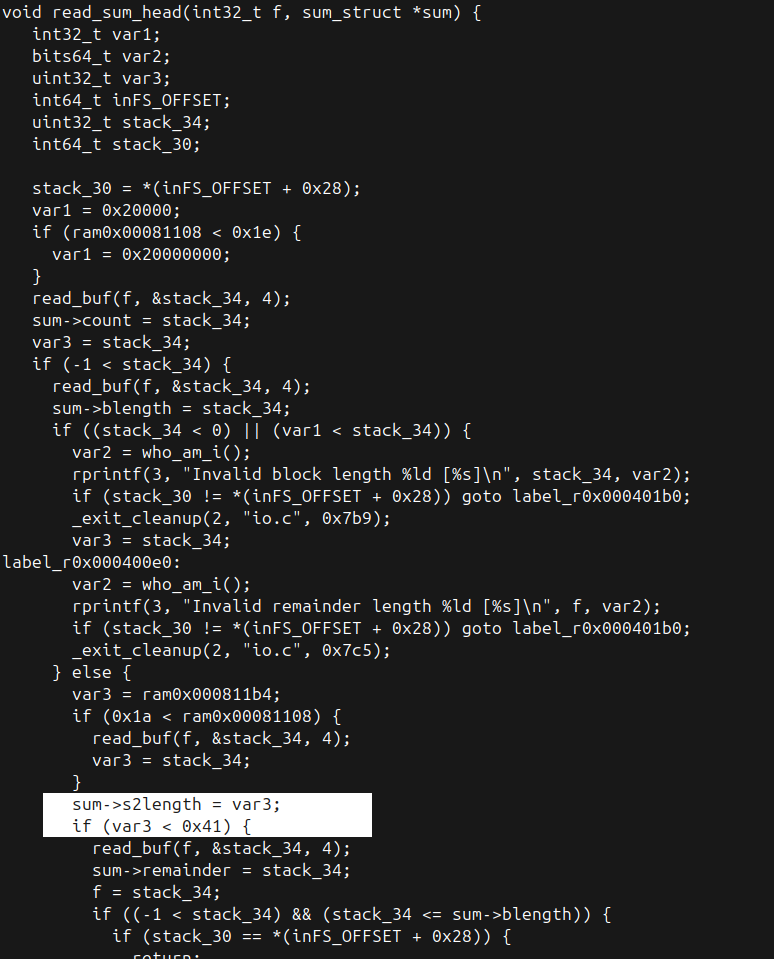

As we previously mentioned, we need to check the value of `MAX_DIGEST_LEN`. This constant is used in the `read_sum_head` function. The following snippet extracted from rsync source code shows how it is used:

if (sum->s2length < 0 || sum->s2length > MAX_DIGEST_LEN) {

rprintf(FERROR, "Invalid checksum length %d [%s]\n",

sum->s2length, who_am_i());

exit_cleanup(RERR_PROTOCOL);

}It wouldn’t be easy to come up with a set of byte patterns to find this comparison in binaries compiled to different architectures. However, our framework is shipped with a decompiler extension that supports powerful queries based on weggli. First, let’s take a look at a decompiled version of `read_sum_head` shown in Figure 5:

We’ll now write a Lua function that will look for the comparison and return its address. The following function does the trick:

function get_digest_len_check(project, faddr)

local decomp = project:decompile(faddr)

local queries = {

[[

sum->s2length = $var;

if ($var < 0x41) {}

]], [[

sum->s2length = $var;

if (0x40 < $var) {}

]]

}

for _, query in ipairs(queries) do

local matches = decomp:query(query)

local max_digest_len_check = matches:address_of_match(2)

if max_digest_len_check then return max_digest_len_check end

end

endThe `get_digest_len_check` function searches for a comparison between a variable that gets assigned to `sum->s2length` and the literal 64. This will make sure our rule only applies to binaries that have `MAX_DIGEST_LEN` set to 64. Because compilers may use a different set of instructions to achieve the same result, the decompiler can also decompile them differently. That’s the reason why we created two different queries and stored them in the `queries` variable, which is a Lua table.

PS.: In Lua, the two brackets create long strings that are allowed to contain newlines.

We use `project:decompile(faddr)` to get the decompiled code of a function. Therefore we should pass a function address to `get_digest_len_check` in its `faddr` parameter and this should be the address of `read_sum_read`. Now we just need to add the following to the beginning of our `check` function:

-- find the address of `read_buf_head` function, where

-- the comparison with MAX_DIGEST_LEN happens

local read_sum_head = project:functions("read_sum_head")

-- if the binary does not have a `read_sum_head` function, return

if not read_sum_head then return end

-- if the comparison with 64 is not found, return

if not get_digest_len_check(project, read_sum_head.address) then return end

-- from this point onwards, we are sure MAX_DIGEST_LEN is 64

-- and can continue with the previous logicThere are smarter ways of doing this, but they involve introducing more concepts and we don’t want to overcomplicate things. But don’t worry, we’ll explore them in the near future.

A vulnerability has more than just description and a CVE number assigned to it. That’s why we support a full range of fields in the table returned to VulHunt. Most of them are self-explanatory:

provenance = {

kind = "posix.ELF",

linkage = "project",

vendor = "samba",

product = "rsync",

license = "GPL-3.0-or-later",

affected_versions = {">=3.2.7", "<3.4.0"}

},

cwes = {"CWE-122", "CWE-787"},

cvss = cvss:v3_1{

base = "9.8",

exploitability = "3.9",

impact = "5.9",

vector = "CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:U/C:H/I:H/A:H"

},

advisory = "https://github.com/google/security-research/security/advisories/GHSA-p5pg-x43v-mvqj",

identifiers = {"CVE-2024-12084", "GHSA-p5pg-x43v-mvqj"},

references = {

["NVD"] = "https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-12084",

["CVE"] = "https://www.cve.org/CVERecord?id=CVE-2024-12084",

["Carnegie Mellon University"] = "https://kb.cert.org/vuls/id/952657",

["RedHat"] = "https://access.redhat.com/security/cve/CVE-2024-12084",

["NetApp"] = "https://security.netapp.com/advisory/ntap-20250131-0002"

},

patch = "https://github.com/RsyncProject/rsync/commit/0902b52f6687b1f7952422080d50b93108742e53",

source = "https://github.com/RsyncProject/rsync/blob/9615a2492bbf96bc145e738ebff55bbb91e0bbee/sender.c#L96-L100",

If you’re in doubt about the linkage field of the provenance table, this is where we tell VulHunt about the context this rule applies to. In most cases, it will contain the value project, meaning it is part of a project or product. There are other possible values, but we’ll skip them for now and focus on our rule!

Now the rule is at the level of completeness you get from Binarly Transparency Platform (BTP). Let’s claim the reward for our work.

If you’ve made this far, congratulations! We did some interesting work together and now it’s time to see the outcome. The video below shows the result when we upload a vulnerable Rsync binary to BTP.

In this article, we showed how to write a VulHunt rule to scan binaries for a known vulnerability using the functions scope and the decompiler extension in standalone mode, but there’s much more to come. VulHunt can scan UEFI components and POSIX binaries within firmware images or docker containers, find unknown vulnerabilities, look for more advanced high-level code constructs, and much more. As a powerful engine, we can’t cover all its features in one blogpost, but make sure you follow us to receive a notification when we release a new article covering VulHunt. Also, we plan to release an open source version of VulHuint in Q2. If you can’t wait, don’t hesitate to contact us to test our platform with your own data.

Introducing VulHunt: A High-Level Look at Binary Vulnerability Detection - https://www.binarly.io/blog/vulhunt-intro

RSync: Heap Buffer Overflow, Info Leak, Server Leaks, Path Traversal and Safe links Bypass - https://github.com/google/security-research/security/advisories/GHSA-p5pg-x43v-mvqj

weggli - https://github.com/weggli-rs/weggli