By Fabio Pagani and Yegor Vasilenko

In the last episodes of our VulHunt saga, we presented the core capabilities of VulHunt and demonstrated how they can be used to write a rule detecting CVE-2024-12084, a remote code execution vulnerability in rsync.

In this new blog post, we will adopt the mindset of a vulnerability researcher and attempt to find a vulnerability in a router’s firmware. We have selected the Netgear RAX30 (firmware version V1.0.7.78) as our target, as it has been scrutinized in the past and is known to include some already disclosed vulnerabilities. Let’s see if we can rediscover some of them!

After unpacking the firmware binary, our attention immediately shifts to the webs/cgi-bin/ directory, which contains several CGI binaries. These server-side binaries handle web requests and are often a source of vulnerabilities. The first step in searching for vulnerabilities is to understand how attacker-controlled input enters the program (sources) and whether it propagates to potentially dangerous functions (sinks).

With this idea in mind, we start to reverse one of the CGI binaries. It quickly becomes apparent that JSON data is expected and parsed from the HTTP request. We also noted the use of several unsafe functions, such as strcpy.

With our reconnaissance complete, the next step is to leverage VulHunt’s taint-tracking capabilities to determine if any identified sources of attacker-controlled input can propagate to our dangerous sinks. We begin by loading the target CGI binary into the VulHunt interactive shell:

:load webs/cgi-bin/rex_cgiNext, we search the binary for functions related to JSON parsing (potential sources) and unsafe memory operations (potential sinks):

vulhunt> %functions json

{

"0x13928": "json_tokener_parse",

"0x13964": "json_object_object_get",

"0x13988": "json_object_array_get_idx",

"0x13a18": "json_object_new_string",

"0x13b14": "json_object_put",

"0x13ca0": "json_object_to_json_string_ext",

"0x13f4c": "json_object_get_string",

"0x13fa0": "json_object_new_object",

"0x140b4": "json_object_array_length",

"0x140cc": "json_object_object_get_ex",

"0x14324": "json_object_object_add",

…

}

vulhunt> %functions strcpy

{

"0x13dcc": "strcpy",

"0x14018": "cmsUtl_strcpy",

"0x756cc": "imp.cmsUtl_strcpy",

"0x75798": "imp.strcpy"

}

vulhunt> %functions strcat

{

"0x13ab4": "cmsUtl_strcat",

"0x13e5c": "strcat",

"0x75840": "imp.cmsUtl_strcat",

"0x75920": "imp.strcat"

}

From this output we select json_object_get_string as our source (as it retrieves data from the parsed JSON), while strcat, cmsUtl_strcat, strcpy and cmsUtl_strcpy are designated as sinks.

Taint-tracking capabilities in VulHunt are implemented using the calls scope, which allows for targeted analysis on function calls within a binary:

scope:calls{

to = <target>,

where = <conditions>,

using = <annotations>,

with = <function>

}

A brief explanation of its arguments:

Using this structure, we can now define the scope that will perform the actual taint-tracking analysis. The combination of scope and check function we produced looks like this:

function check(project, context)

if context.inputs[2].annotation == "out" then

print("WOOT", context.caller.address)

end

end

s = scope:calls{

with = check,

to = {

matching = "strcpy|cmsUtl_strcpy|strcat|cmsUtl_strcat",

kind = "symbol"

},

where = caller:calls "json_object_get_string",

using = {callees = {json_object_get_string = {output = var:named "out"}}}

}

This rule effectively annotates the return value of the JSON-retrieval functions with the taint tag out and then checks if that tainted data is ever passed as the source string (the second input) to any of the unsafe sink functions, printing the caller address if a successful taint-flow is detected.

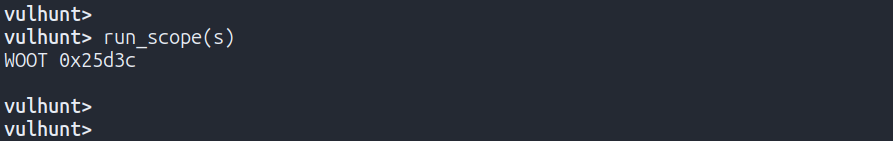

After running the scope in the VulHunt shell, we can see that one match is detected!

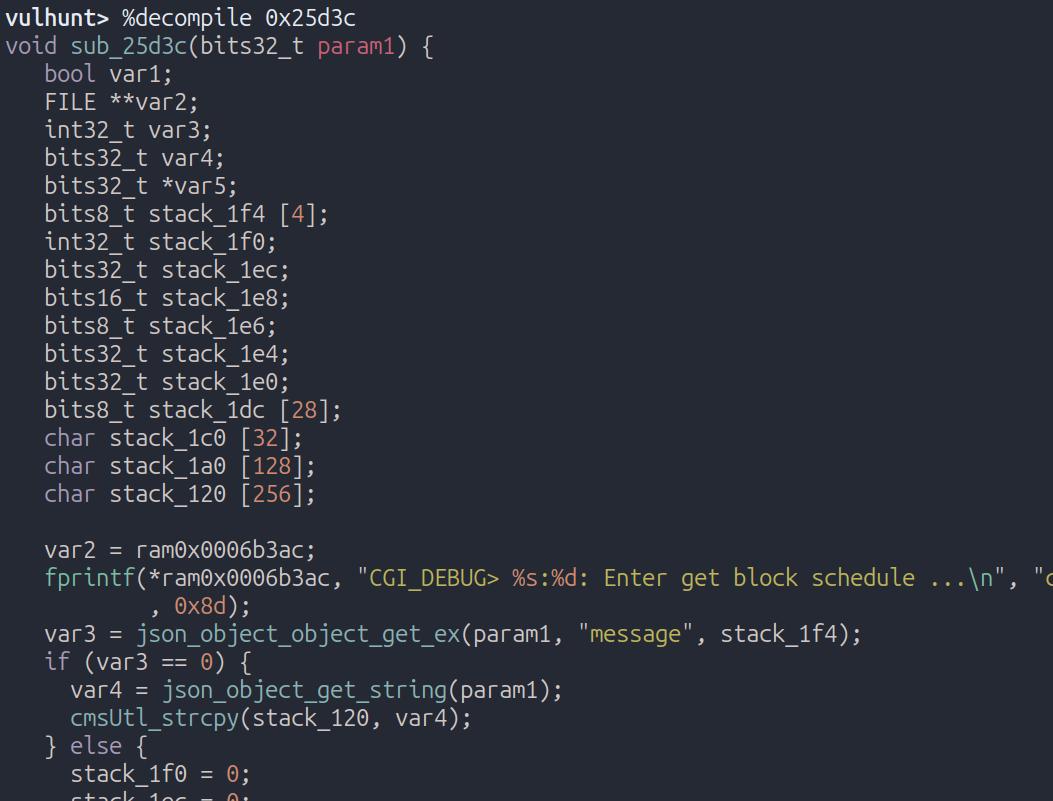

When decompiling the caller function at 0x25d3c we can immediately spot the vulnerability:

The scope we created in this blogpost successfully re-discovered CVE-2023-48725, which was initially documented by Cisco Talos.

While the VulHunt interactive shell is an excellent environment for rapid prototyping and validation, a VulHunt rule is necessary for scanning hundreds of binaries automatically with the VulHunt engine. To make this transition, we add a few essential elements to our working prototype. First, we add the required metadata fields that define the rule:

author = "Binarly REsearch"

name = "JSON input to dangerous function"

platform = "posix-binary"

architecture = "*:*:*"

These fields are largely self-explanatory. The architecture field is a triple, where the use of asterisks (*:*:*) ensures the rule applies to every binary, thus maximizing coverage.

Next, we add one more source (json_object_to_json_string_ext), a few more sinks (such as system and sprintf) and we upgrade the check function to generate a structured vulnerability finding instead of just printing an address. The result object, returned by the check function, enhances the finding with triaging information:

scopes = scope:calls{

with = check,

to = {

matching = "strcpy|cmsUtl_strcpy|strcat|cmsUtl_strcat|system|execve|memcpy|memmove|sprintf|snprintf|strncat|strncpy",

kind = "symbol"

},

where = caller:calls "json_object_get_string" or

caller:calls "json_object_to_json_string_ext",

using = {

callees = {

json_object_get_string = {output = var:named "out"},

json_object_to_json_string_ext = {output = var:named "out"}

}

}

}

function check(project, context)

for _, src in ipairs(context.inputs) do

if src ~= nil and src.annotation == "out" then

local source_addr = src.origin.source_address

return result:critical{

name = "BRLY-HUNT-1234",

description = "Buffer overflow: unsanitized JSON string passed to unsafe function",

cwes = {"CWE-120", "CWE-676"},

evidence = {

functions = {

[context.caller.address] = {

annotate:at{

location = source_addr,

message = "Source: attacker-controlled string from JSON parsing"

}, annotate:at{

location = context.caller.call_address,

message = "Sink: potentially unsafe operation on an attacker-controlled string"

}

}

}

}

}

end

end

end

The main part of the result is the annotation within the evidence block. This allows VulHunt to mark the exact instruction addresses for the source and sink, embedding the security finding directly into the decompiled code. This drastically accelerates the triaging and explanation of the vulnerability. The rule is now ready and can be used to automatically check any router firmware and discover new vulnerabilities across hundreds of binaries.

Running this rule on the firmware binary returns 24 findings. After manually analyzing each of them, we deemed that they are all benign usages of sources and sinks and do not represent a security issue, except for two findings.

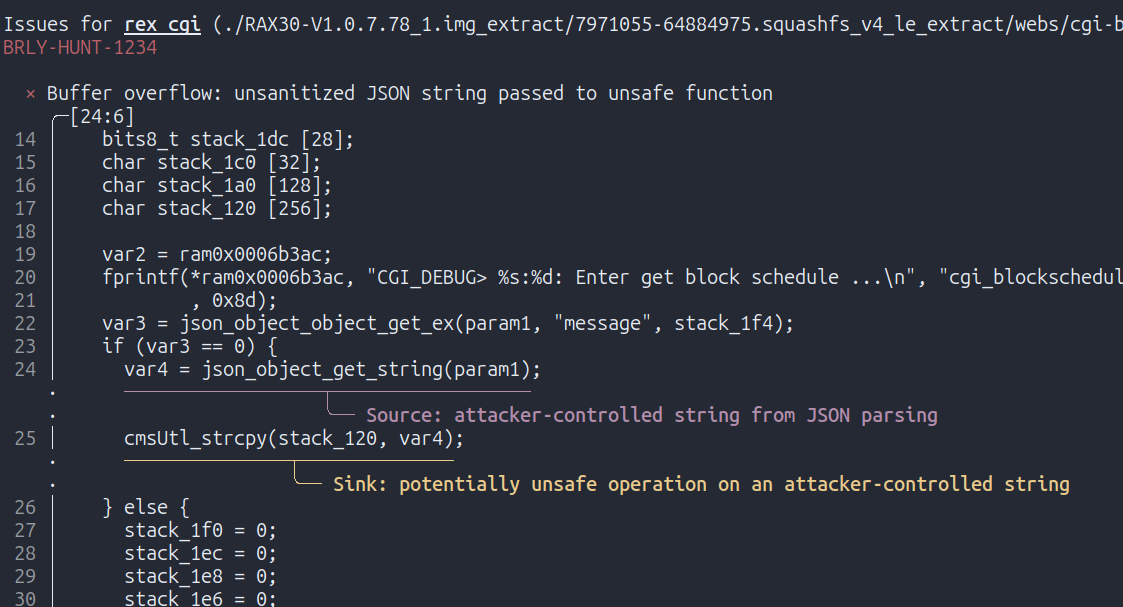

The first one is the issue we detected previously with the scope, this time with clear annotations:

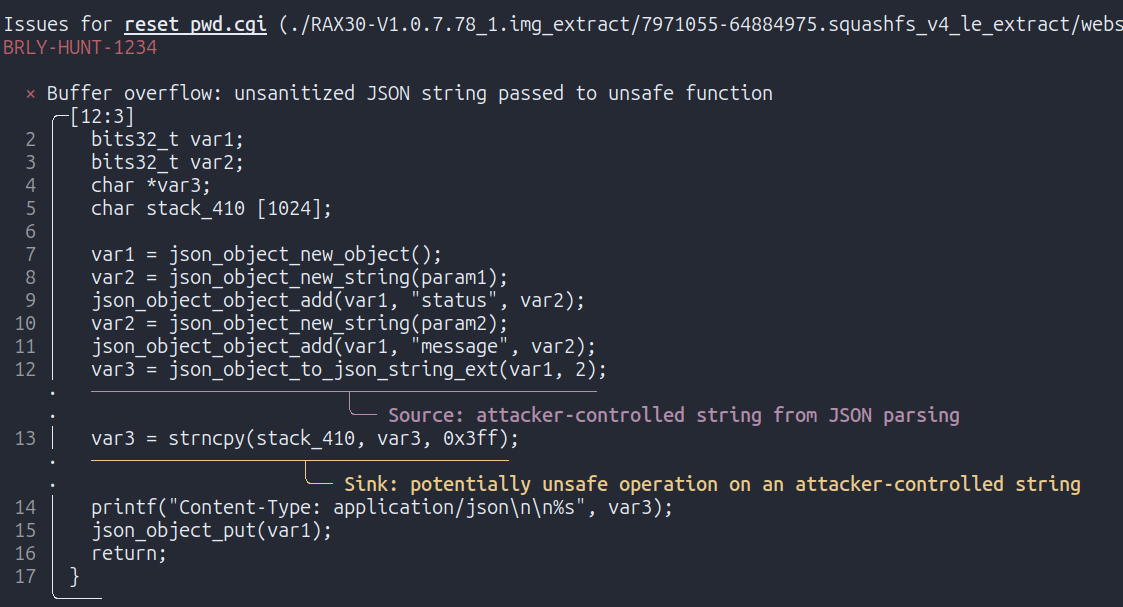

The second finding shows how attacker-controlled data is copied into a stack-allocated buffer using strncpy. This is problematic because the code doesn’t add a NULL-terminator after the copy, which causes the subsequent printf call to leak stack memory to the client until a NULL byte is encountered.

This also represents a known vulnerability, previously discovered by NCC Group.

However, this known vulnerability demonstrates one of VulHunt's key capabilities: scalability. While the initial report identified only reset_pwd.cgi, our rule automatically produced findings for three other CGI binaries (tm_block.cgi, rex_cgi, and debug.cgi).

In this blog post, we successfully put ourselves in the shoes of a vulnerability researcher demonstrating the full workflow from rapid prototyping a taint-tracking scope in the VulHunt interactive shell to creating a robust rule capable of scanning at scale.

In the next blog post, we take a deeper look at how VulHunt works under the hood, covering its dataflow analysis, code pattern matching on decompiled code, type libraries, function signatures, and IR-based detection that together enable vulnerability detection in binaries. We also explore how these capabilities combine to make findings not just accurate, but explainable and actionable for security teams.